Too Much Oil with Nowhere to Go

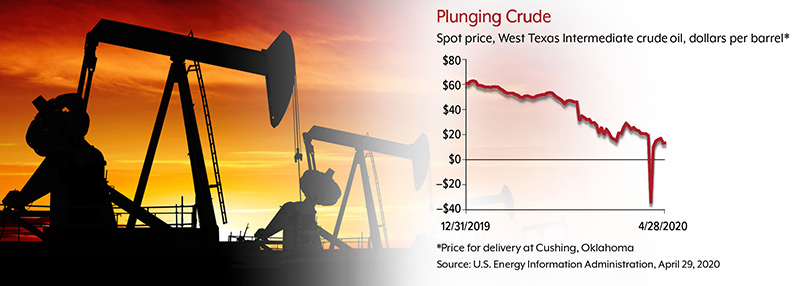

On April 20, 2020, the price of a futures contract for West Texas Intermediate crude — the benchmark for U.S. oil prices — fell below zero for the first time in history, dropping more than 306% in trading on the New York Mercantile Exchange and ending the day at –$37.63 per barrel.1 Essentially, this meant that investors who would soon be obligated to take possession of a barrel of oil were willing to pay someone else to take it instead.

This unprecedented price collapse was for contracts scheduled to expire the following day and require delivery in May. June futures dropped 18% to about $20 a barrel, and the May contract clawed its way back to about $10 on April 21.2–3 But the dramatic plunge below zero highlighted a fundamental problem for the oil industry in the face of evaporating demand due to COVID-19. There is too much oil, and the industry is running out of places to put it.

Supply Without Demand

The International Energy Agency estimates that global demand for oil dropped by 29% in April 2020 compared with 12 months earlier and will drop by an average of 23% for the second quarter — equivalent to losing all of the oil consumption in the United States and Canada.4–5 The historic agreement by Russia, Saudi Arabia, and their allies (OPEC+) to reduce production beginning May 1 — equivalent to about 10% of global production — will help, but won’t be soon enough or large enough to stop the continuing expansion of supply, and storage facilities are filling up fast around the globe.6

The pressure is especially acute on West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude and other U.S. oil stored for delivery in tanks at Cushing, Oklahoma. Under normal circumstances, oil passes through Cushing to refineries, but with diminished demand, the Cushing tanks are expected to be full sometime in May. Land-locked oil like WTI has nowhere else to go, which is one reason why traders were willing to pay to avoid taking delivery.7

A large exchange-traded fund (ETF) holding crude oil commodity futures contracts also played a major role in the rush below zero. ETFs hold futures strictly as paper investments with no intention or capability of taking delivery of oil — there are no storage tanks on Wall Street; they typically roll each month’s futures contract to the following month. But with no one willing to buy the May contract and accept actual delivery of oil, the ETF was forced to pay to get rid of the contracts. With storage problems likely to continue, June futures may face the same extreme price pressure as May.8

Brent Crude and Floating Storage

Whereas WTI contracts require accepting delivery of oil, contracts for Brent crude — the global benchmark — are settled in cash and unlikely to go negative. However, the physical price of Brent, which is pumped out of the North Sea, is already low and may go lower as storage tanks on the shore fill up, waiting for the oil to be loaded onto tankers. Like WTI, Brent is high-quality oil, and other grades are typically sold at a discount to the benchmark. If Brent drops to $10, for example, oil from Saudi Arabia or Iraq could be priced below $0.9

The oil glut has created a record imbalance between near-term and long-term oil contracts, as traders anticipate increased consumption in the future. The disparity is great enough that some trading companies are buying cheap oil now and storing it on huge tankers that can carry 2 million barrels of oil.10 It’s estimated that a third of the world’s tanker fleet may be used for storage instead of transportation if the crisis continues.11

Not Worth Pumping

Oil prices are often volatile, but the dramatic drop in 2020 has been extraordinary, driven by the global pandemic shutdown and a price war between Russia and Saudi Arabia. On April 28, after the subzero dive had come and gone, the spot price for WTI — the price actually paid on delivery in Cushing — was $12.40 per barrel, down 80% for the year. The spot price for Brent was $15.60 per barrel, down 77%.12

At these price levels, it is no longer profitable for many producers to pump oil, especially for the more expensive shale-oil production methods used in the United States. In the four-week period ending April 17, U.S. oil production dropped by 900,000 barrels per day, about 7% of production and the largest one-month drop since the Great Recession. Some analysts expect an additional drop of 2 million barrels per day by year-end.13

Layoffs and rig closures have begun and are expected to expand quickly. Although large companies are likely to weather the storm, some smaller producers may be forced into bankruptcy. The U.S. Department of Energy has opened 30 million barrels of storage in the Strategic Petroleum Reserve for lease to private companies — equivalent to about 2.5 days of U.S. production — and plans to accept another 47 million barrels to fill the reserve to capacity; as of late April, no funding to purchase oil was available. Other forms of government support are being considered.14–16

Signs of a recovery in demand for oil in China have sparked some optimism, but the tension between supply and demand will continue to evolve, and extreme price volatility can be expected until the market finds balance through production cuts and/or rising demand.17

For now, keep in mind that oil prices are only one of many factors influencing the markets and the global economy. It’s important to maintain a long-term perspective and continue to focus on your own investment goals.

Sources:

1–3) MarketWatch, April 20 & 24, 2020

4) International Energy Agency, April 2020

5, 12, 16) U.S. Energy Information Administration, April 2020

6–7) The Wall Street Journal, April 22, 2020

8–9) Bloomberg, April 20 & 22, 2020

10) The Wall Street Journal, April 20, 2020

11) OilPrice.com, April 22, 2020

13) CNBC, April 22, 2020

14) CNN, April 21, 2020

15) U.S. Department of Energy, April 2, 2020

17) The Wall Street Journal, April 23, 2020